At the intermissions of Tristan und Isolde Friday (dress rehearsal) there was madness in the air, a place rife with miscommunication. Wagner himself said that good performances would make people mad (or crazy), so perhaps that was the problem. A crappy production would have been safer, so maybe the COC should have a disclaimer above the door (“this production may impair your judgment, operation of heavy machinery not recommended”). We’d been taken into a place of magic and fantasy, where drinks don’t poison you so much as open doors to other realms and dimensions.

Miscommunication is of course something central to Tristan und Isolde. The story is built out of a series of them. More fundamentally, however, this is a place of honour, which means that people often hold a great deal of their feelings in reserve. In a traditional Tristan Isolde rails at the stoic knight in Act I, finally demanding he drink atonement because he’s doing the safe and politically correct thing.

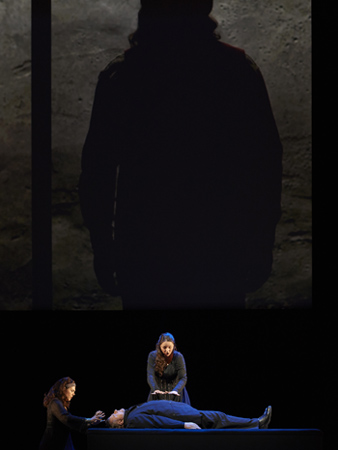

Thumbnail: Video still by Bill Viola, from the Opéra national de Paris production of Tristan und Isolde. Photo: Kira Perov © 2005

Peter Sellars defies most of the usual logic in his production that’s come to Toronto after an earlier incarnation in Paris seven years ago. With the use of elaborate video, Sellars changes the usual balance. A conventional Tristan sees characters speak indirectly, often across great distances from opposite sides of the stage, before finally being compelled by a potion to be truthful. It’s called a love potion but it could just as well be truth serum.

Sellars changes it up. His characters sing Wagnerian phrases from intimate distance. Simply from the point of view of intensity it’s almost hazardous, imagining Ben Heppner taking Franz-Josef’s heart-break from inches away, right into his face.

While Tristan is often spoken of as an opera about love, I think it’s a misnomer. Wagner was obsessed with Schopenhauer, and in this opera uses the medieval legend about the lovers to create a parable about the Buddhist ideas he was discovering at this time. Chief among the tenets of this philosophy is the futility of desire, that we are to overcome desire, and that death is our release. The opera uses love as a pathway to enlightenment for both of the lovers.

Bill Viola’s video seems very well attuned to Schopenhauer. While Wagner’s music captures the Dionysian intoxication of desire, Viola gives us the deeper structure, the quest of each for the other.

While I would wish it were somehow recorded in a DVD I don’t think it can be properly captured, given that there’s so much to look at. The eye sometimes doesn’t know where to go, which text (music, singing, words, or visual images) to follow. It’s delightfully challenging.

And I must see it again.